Save StorySave this storySave StorySave this story

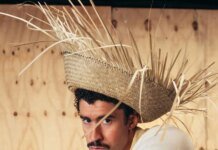

Jack Conte hates the word “influencers.” As the CEO of Patreon, he would rather people call artists “creators” if what they do is build loyal fanbases willing to pay for what they do online.

While platforms like TikTok encourage their power users to sell doodads on the TikTok Shop, Patreon wants people to buy into the platform’s stars. To pay a few bucks a month to read what they write or listen to what they have to say.

It’s an idea that took root on a much earlier version of the internet. When Conte confounded the company with his college roommate in 2013, he was just trying to promote his band. Monetizing their videos on YouTube wasn’t cutting it, and Conte needed a platform that would allow his fans to support the band through more than just streams. Thus, Patreon was born, allowing Conte to essentially turn his band—and many other artists—into subscription-style services.

The company has charted impressive growth over the past decade and now pays out over $2 billion a year to creators who use its platform. And as the online creator ecosystem has morphed in recent years, Conte’s vision has evolved along with it: He’d like to set the “TikTokified” internet on a different course, away from content optimized to keep people on their phones and toward one that keeps people connected to artists they love.

For this week’s episode of The Big Interview, I spoke with Conte live in San Francisco for an event WIRED held in partnership with the city’s public radio station, KQED. During our conversation, the Patreon CEO talked about ChatGPT, Prince, and the differences between influencers and creators.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KATIE DRUMMOND: Jack, thank you so much for being here.

JACK CONTE: Hello.

Before we really get too far into it, we always start with a little bit of rapid-fire questioning, some warmup. Jack, what is the most active text thread that you're on?

I am not on any active text threads. I try to do as little of that as possible.

OK, we may come back to that later. What does the algorithm know about you?

Way too much.

Oh yeah, I know the feeling.

It knows that I got a new dog recently.

What kind of dog?

She’s a mutt. She is a little bit of a golden retriever, a little bit of Chihuahua, some pit bull. She's the most beautiful creature in the world.

I also have a pit bull mutt. Are you getting ads for dog food now?

Yes.

I get it. What is a piece of tech that changed your life?

DAWs, digital audio workstations. The transition from having to have half a million dollars of recording gear to make an album to being able to make an album on your laptop is the most beautiful, wonderful thing in the world.

What is your favorite way to spend a Saturday in the Bay Area? I have to ask, you're from here, and of course we are here.

Sorry to bring up the dog twice, but she just learned that she can run straight into the ocean. And it's so great. I love it. And so I throw sticks for her into the ocean. She bolts into the ocean, totally fearlessly swims around, looking for it. Best thing in the world.

What music app do you use the most?

Spotify.

Let's give our audience a little bit of your backstory, just in case they don't have it. So you were born and raised here in San Francisco, and music has always been in your life. You studied music at Stanford, you founded Patreon with your old college roommate in 2013, and that was in response to a personal experience, right?

Yes, so I have a band called Pomplamoose, which we started in 2007, 2008—right at the beginning of creators before the word creator existed. We were uploading and reaching a community and building a fanbase and putting our music online, and it was working and wonderful.

But the business model around being an early creator on the internet in 2010 meant we had to jump through a million hoops. We had to build our own website. Which worked, but it was like everything was bespoke and we had to do everything ourselves.

Yes.

It's hard to go back 15 years now at this point, but there was a period where the term “creator economy” didn't exist. If you told the platforms that you would like to be paid for uploading work to their platform they'd say, “Oh, you don't have to upload work to our platform.” And we'd be like, “Yeah I know, but I am and it's building a lot of value for you, and it'd be nice if I got paid.”

That was really frustrating for me as a creative person, because what I was seeing from my end was: You upload a video, get a million views on that video, there'd be 10,000 comments. Then I'd get my ad revenue check for $180 at the end of the month, and I'd be like, “This is fucking crazy.” That felt really bad to me as a creative person, as an artist. So yeah, that's where Patreon came from.

In 2019, WIRED, always prescient I like to think, did a feature on you and Patreon. And the subhead on that story reads as follows: “The DIY musician's membership platform set out to provide a livelihood for artists on the internet. Is it more than just a band-aid for a broken system?” How would you respond to that question today?

The system is broken. Now there are a number of systems that are broken for artists and creators. I would still argue that the platforms undervalue creative people and media makers, which is, I think, just a cultural thing in tech, honestly.

Say more.

I don't think of Patreon as a band-aid—surprise, surprise—and maybe the reason why is because what we want to do is change the way the internet works. Specifically, there's a new problem that we've been tackling over the last five years, which is that the internet has been TikTokified. It moved from being a follow-based subscription system where you would choose who you want to interact with into an algorithmically curated format where you don't decide what you see—the platform decides what you'll see.

Right.

The net result of that is you see 500 creators in one day, and instead of forming deep relationships with those creators, you just skim the surface. That is bad for fans, because I think you lack the depth of connection with one person over time. It's bad for creators, because it makes it really hard to build a business and a community. If you can't keep in touch with your fans, how can you have a community? How can you have a business? How can you sell concert tickets? How can you go on tour? So this has become a very important problem for our creators and something that we wanna change about the way the internet works.

You've paid out a mind-boggling amount of money. It's $10 billion, right?

Yeah, we just crossed $10 billion paid out.

It is proof that art and artists are valuable. That's what it is. People who have something to say and are creative and stand on the shoulders of giants and do something differently and take risks and try things and build communities—it's proof there is value in that. As an artist, it's so easy to look at these frickin' dashboards. You take out your phone, you look at your view count, you look at your like count, you look at your ad revenue. You do that for seven or eight years and you start to feel worthless in those systems as an artist. And so what feels so good about hitting $10 billion is that it's not that art isn't valuable, it's that those systems are dumb and need to be changed.

So the TikTokification, how do you solve for that?

There's a couple key things. The main overarching thing is you build a system that isn't singularly focused on maximizing human attention. Most of the internet is singularly focused on optimizing one metric, time spent in that app. Say what you want about that. It's had some pretty horrible effects on people.

I think humanity is having a rough entrance into the information age. I have to set a time limit for myself on some of these apps, because I'm sucked in my phone, and I know what's going on, and I'm still sucked in. I hate it. I don't want that. Time spent creates all types of perverse incentives for the platform, for the consumer, for the advertiser, for the creator. And what you end up with is stuff that you pay attention to instead of stuff that has value. That is bad for people, and it should change.

I hear you.

So what we want to do is build a system where the incentive stuff is valuable. Media that is valuable, stories that are valuable.

How do we measure value? Instead of optimizing around whatever I will pay attention to—which actually is just hacking the human limbic system and A-B testing your way to the bottom of someone's brainstem and figuring out what will suck them in—we’re looking at what will someone pay for? What makes someone go deeper with a creator over time—eight weeks down the road, a year down the road, two years down the road. What makes someone trust a person so much that they're interested in the recommendations from that person? How can we build a system that optimizes for long-term human connection and deep relationships instead of just addicting people to their phones?

I want to ask you about the influencer-ization, which is a word that I made up …

Solid word.

Thank you. Patreon has obviously tracked closely with the expansion of this idea of being an influencer very closely. I would say that you were also integral to that phenomenon booming in the first place. And it's not just musicians. It's musicians, comedians, self-help gurus, podcasters, journalists.

Not everyone is a fan of that trend, right? I think there are gives and takes and pros and cons. I could tell you within the field of journalism to be publishing the kind of journalism that we publish at WIRED, and then to realize that someone with no credentials, with no training, with no actual reporting, is playing the part of newscaster and is reaching and finding trust with hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of people. Maybe they're pocketing money from the DNC and not disclosing it, which is a story that WIRED published recently to much controversy.

What do you make of that? What role does Patreon play in trying to make sure that the influencer-ization of the internet is in service of that healthy ecosystem that you are seeing?

Couple thoughts on that. Before I get to the meat of that question—the word influencer. I really hate that word. I hate it, and I don't use it.

So creator, not influencer, for you.

Creators. And I think there's a difference in the way I think about it. There's a big difference. Influencer is such a bad word.

It's not actually my word. I just added the thing to the end of it.

No, it's no knock on you. It is such [a reflection of] the way a brand thinks about an artist. What is the commodity in you that I can extract and use for my benefit? It is your influence.

But a lot of people take great pride in being an influencer.

Yes. And actually the people that do the best on Patreon, I think that person feels more like a creator and less like an influencer. I'm not saying there aren't any influencers on Patreon. I am sure there are. But the interesting thing about Patreon is what people will pay for, which is a decision that you make with your forebrain. You don’t make it with your lizard brain.

With this brain [Makes phone-scrolling gesture].

Exactly. It's like, what is so important to me that I want to pay five bucks a month? If you think about the companies that have instituted consumer payments into their media offerings, they are companies that focus on making really high-quality stuff. The New York Times is an example, or The Guardian is an example.

Then there's a bunch of creators who have a paid offering. You only convert on a paid offering if it's worth paying for, which means it's valuable to the person who's getting it. I would offer a lot of the time that what you're bucketing as an influencer is a bit of a come-and-go, clickbait, fast-dopamine-hit kind of function. You can do that on YouTube, you can do that on Instagram. But I don't know that you can build a deep lasting business and community around that as much as you can by focusing on high-quality media.

I am guessing some people tuning in to this interview are doing so because they want to be successful on Patreon. Whether they conceive of themselves as influencers or as creators, they see that career path. Ask my 8-year-old. This is the only thing they're interested in doing with their lives. What advice do you have for those people? Whatever field they're in, what do they have to do to be truly successful, to make this a career, to give this actual depth?

Don't compromise. Make something beautiful. Make something important. Make something that you love, deeply care about. Be careful with writing to the internet algo and getting the clicks and getting hits. It's an easy way to get started. I'm guilty of it. I have done that. And it's a good tool in your toolkit. But every time I've over-rotated in that direction I look back at the end of three years and I have this feeling of like what the fuck am I doing with my life? Why am I making all this stuff that I don't even care about but that will perform? That outcome-oriented artistry is not why kids get into the game of being an artist.

David Bowie and Prince and Ella Fitzgerald and Elle Mills and Hank Green. These are people who say something with their work, and I see what they say and I feel connected to them. So my advice to people who want to be artists is: Say something. Say something important. Say something that is meaningful to you. Express something that you're a little scared to say. Something that's a little bit risky. There's value in that. And you will find a path to making everything else work.

You're talking a lot about human-created work, human connection. As you're talking, I can picture a version of the internet as you describe it. Which brings me to AI. Obviously WIRED and everybody else has been covering the hell out of AI, but in particular, copyright lawsuits against companies that have trained their models on the IP of creatives, of creators, of authors, of journalists, of musicians. Talk to me about how you are thinking about artificial intelligence in the context of Patreon, in the context of the internet that you want to see. What are the risks to you? What are risks to the creators that you support?

I mean, this could be a whole podcast. First things first. I think it's crazy that creators' work is being used to train these models and then generating hundreds of billions of dollars of value, and creators are not partaking in that value creation.

It is crazy.

There's a piece of me that can actually feel myself going back to 2012 when Patreon started. It's the same thing, right? The same thing's happening again. So it's personal for me. I remember when we did this the first time. I remember the Viacom lawsuit against YouTube in 2007, and that took seven years, and then eventually there was a system that compensated rights-holders, and it wasn't perfect, but at least they got to partake in the value that was being created.

I believe and hope there will be such a system for creative people with regard to AI. There are two problems. Creators are having their work used without their permission. There ought to be a way to opt out. And two, creators are having the work used without compensation. There ought to be a way for them to get paid. It's that simple. We’ve figured out how to do a lot of crazy shit. We're sending rockets into space; we got self-driving cars. We should figure out how to get creative people paid for their work.

It's a shame, because the technology is really cool. I use ChatGPT all the time. It's amazing. It's useful. And I think there's a lot of implementations of AI that are really great. I just wish we were rolling it out in a way that wasn't kind of at war with creative people, which is the way we did the first version of the internet.

Do you have rules of the road for the creators on Patreon around how they do or do not use artificial intelligence? I mean, I'm thinking about it in the context of journalism. We have guidelines. You can do this with AI. You cannot do this. You cannot write your story with artificial intelligence. What does that look like for you?

So we don't disallow creators to use AI. I think we're starting to finally see some artists use AI in a really cool way. So we don't prohibit AI by any means, but we don't train models on creator-generated works; we don't do that stuff.

Honestly, part of the reason is because AI is more of a brand than it is a technology at this point. I know the electricity metaphor is a little bit overused, but like it's kind of in everything now.

Right.

The one thing I will say about the way AI is being used right now, just artistically, is when the motion picture camera first came out in 1895 it was called a Cinematograph. If this was a theater where there was a play, it would go to the middle row. They'd put a wide-angle lens on the camera, and they would film the play from like 20 feet away. Then they would play that film back for audiences. Audiences were like, “This is black-and-white. It's 2D and it has no sound. This film technology is not going anywhere.” Because the artists at the time, the filmmakers, were using a new medium, but the only thing they could think of was plays. I think a lot of creators are using AI like that now.

Yeah.

It's the version of the Cinematograph plopped in the middle of a theater where it's like, “Oh, let's try to make a movie. Let's try to replicate a shot that you would take with a camera.” I don't think that's what AI-generated work is gonna look like in five years, 10 years. The most emotionally resonant work is going to be nothing like movies or images that we know or think of. It's not going to be in that box. It's going to be something surrealist and incredible and mind-blowing. And I'm actually pretty excited to see what a good use of that medium looks like from an artistic standpoint.

I guess we'll have to find out.

I want to ask you: You were making music and decided to start a company. It obviously worked out for you. You now have over 400 employees, multiple offices. So you went from Jack the music dude to CEO of a serious thing. You were the CEO of a serious company. Talk to us about that learning curve.

This is what I talk about with my therapist regularly. So, not easy. It was sitting around a table full of VCs, doing a pitch, and feeling like I'm a fucking YouTuber pitching a tableful of VCs. That shifted to slowly figuring out what works and how, and learning a lot, reading a lot. Kind of just like everybody else does. At this point we're 12 years in. I don't claim to be an expert at this, but I do feel a sense of like, OK, I know what to do now, which is a good feeling. I'm often wrong still, but I know spiritually what I want for Patreon.

There are a few things that you could do with your company that you haven't. You have not IPO’d. You are still a privately held company. You have not been acquired. You have acquired many other companies. So in a few different respects, I think Patreon has behaved quite differently than other tech companies. And you behave differently than other CEOs. Why not IPO, run away with a few billion dollars, buy a jet, get a second house?

What a great idea. I'll be right back.

But why not? You could have done it. You can still do it. Do you think about it?

Of course. The real answer is because it's not the right time yet. And I want Patreon to be in charge of its own decisions and mission and destiny. So part of the reason that we haven't been acquired yet is because there's very few potential acquirers where I feel like they would do right by what we're trying to do. I don't wanna do that. So that's why we haven't been acquired. In terms of going public, we don't have plans to go public. I do hope one day that Patreon is like an independent publicly traded company. I think it's probably where Patreon will end up. Of all the paths for Patreon, I think that's the best, strongest path for us—to be in charge of what we want to do in the world.

Before we end, I am going to force you to play a brief game. It's called Control, Alt, Delete. It's like the nerd version of Fuck, Marry, Kill.

Great game.

So I want to know what piece of tech you would love to control. What piece would you alt, so alter or change. And what would you delete? So what would you vanquish from the Earth if given the opportunity?

I totally should have thought of this ahead of time.

You should have, but it's live now. So, control.

I would control the distribution platforms for creators to get their work out there.

Very nice. What would you alter?

I'm going to be so boring.

Oh, you're not boring. You've been very entertaining.

This is actually what I would do: I would just save us all seven years of a Viacom lawsuit, The New York Times lawsuit, and I would pay creators when their work is used in AI. I will alter the AI platforms to pay creators.

Well, wouldn't that be nice? What would you delete? What are we getting rid of tonight?

Just to be spicy and to kind of fuck with things, let's delete mobile phones.

Just get rid of them?

Yeah, I'm fucking tired of looking at my screen all the time.

How to Listen

You can always listen to this week's podcast through the audio player on this page, but if you want to subscribe for free to get every episode, here's how:

If you're on an iPhone or iPad, open the app called Podcasts, or just tap this link. You can also download an app like Overcast or Pocket Casts and search for “uncanny valley.” We’re on Spotify too.